Brian Giesbrecht is a retired judge of the Provincial Court of Manitoba, Nina Green is an independent researcher, and Tom Flanagan is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary.

May 27, 2022 will mark the one year anniversary of a shocking event that changed the course of Canadian history. Last year on May 27th, Chief Rosanne Casimir announced that ground penetrating radar (GPR) had detected the remains of 215 children who had died at the Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS) under sinister circumstances. More shocking still, Chief Casimir claimed that children as young as six had been awakened in the middle of the night to secretly bury these children in the apple orchard.

The nation was thrown into a frenzy of self-flagellation. The Prime Minister had the flag lowered – where it stayed for six months – politicians openly wept, orange shirts were worn, monuments of small shoes appeared spontaneously all across Canada, churches were burned and vandalized, condemnations were issued by the Pope and world leaders, and lawyers immediately filed a complaint with the International Criminal Court at the Hague.

The world was subsequently told by the media and Indigenous leaders that the human remains in Kamloops represented only a small number of thousands of such burials at former residential schools across Canada, and the federal government committed $321 million to GPR searches for unmarked graves.

Yet strangely, to date no actual proof of human remains has been found anywhere.

Over the course of the past year, hundreds of negative articles were written in which Chief Casimir’s claim that the remains of 215 children had been discovered at Kamloops were accepted as fact. Additional criminal acts were alleged. In the CBC’s Fifth Estate program in January, the school was described as a place of horror where children mysteriously went missing, bodies were seen hanging in barns, children were sexually abused, and burials took place at night.

But is any of this true, and if so, where is the evidence?

It is noteworthy that none of these hundreds of articles referred to the fact that many accomplished people who attended, or taught at, the Kamloops Indian Residential School made no reference to anything dark or evil, much less murderous.

Len Marchand, for example, the first status Indian federal cabinet minister, transferred to KIRS by his own choice in 1949. In his autobiography he explicitly refused to say anything negative about the school, his only complaint being that the potatoes were watery.

Three Indigenous teachers – Joe Stanley Michel, who graduated from KIRS, Benjamin Paul, and Mabel Caron – were on staff in 1962 when the CBC filmed a documentary at the Kamloops school, and none complained of anything untoward, either then or later.

By 1973, half the staff at KIRS was Indigenous, and none of these Indigenous staff members complained of anything untoward at the school, neither then nor later.

It is also noteworthy that none of these hundreds of articles mention any of the positive aspects of life at KIRS, including sports teams, musical and dance groups, picnics, socials, parties, Saturday night dances, and the spacious and comfortable student hostel built in 1962 – all while these alleged secret nighttime burials were taking place.

Nor do any of these articles mention the fact that at that time the school had an impressive outdoor swimming pool, as shown in the photograph at the head of this article. Kamloops was one of at least three British Columbia residential schools with swimming pools. According to an announcement in the Indian Record in June 1959, the Kamloops pool was one hundred feet long, and was thus at least as large as the Centennial Pool built for the residents of Kamloops in 1958.

Sports teams, parties, and swimming pools don’t support the narrative about residential schools that today fills print and social media spaces – namely that these schools were places of horror where children were starved, abused, murdered, and secretly buried.

That is in large part because historical documents portraying the positive side of residential school life have been largely suppressed.

The most revealing of these documents are the chronicles kept by the orders of Sisters who taught, nursed, and cared for the children, and the codices of the Oblate priests who administered the schools and were largely responsible for preserving Indigenous languages in Canada. These historical documents do not support the story of misery, abuse, neglect and murder now almost exclusively told, and for that reason have been suppressed and treated as though they do not exist, even though the National Centre for Truth and Reconiliation (NCTR) has had almost all of them in its possession for years.

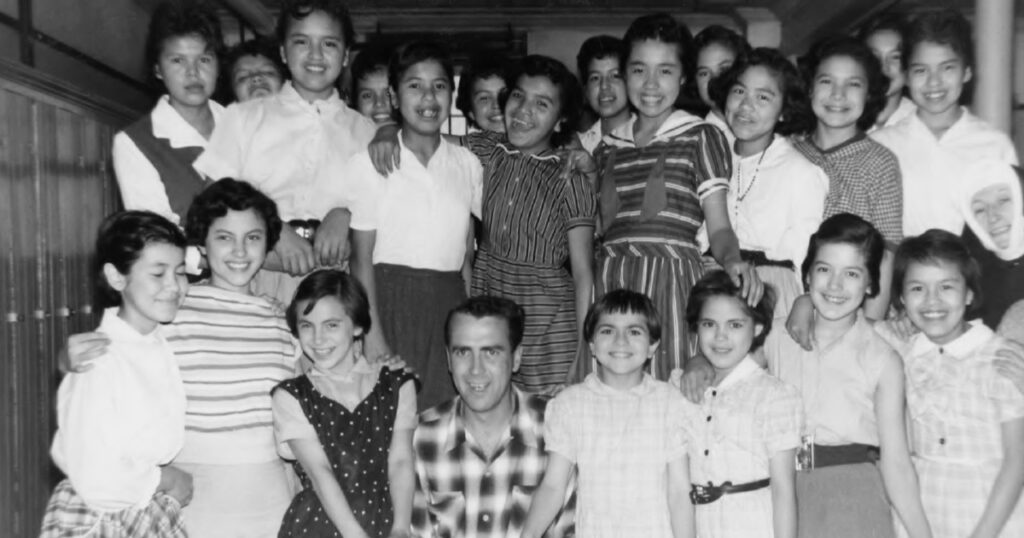

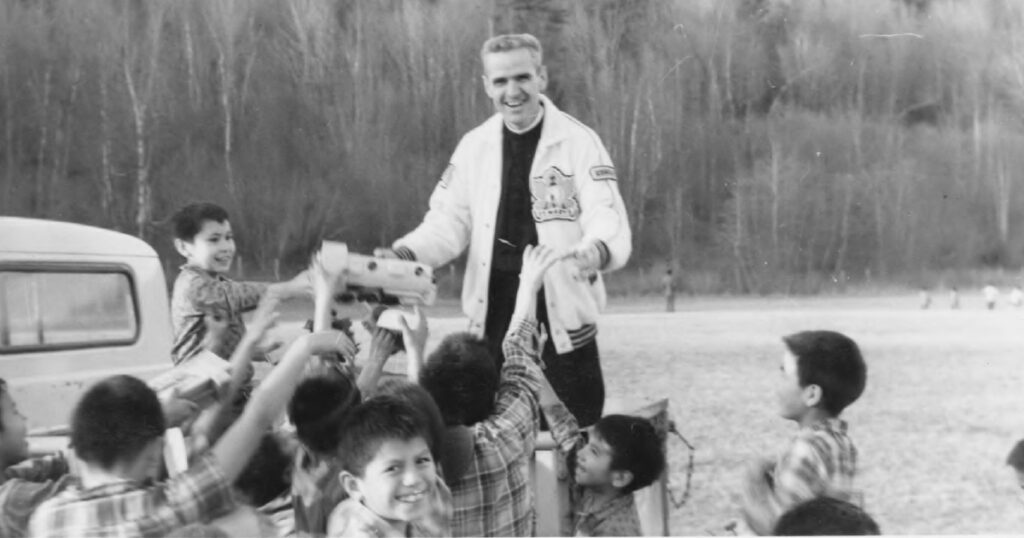

Similarly, photographs of children at residential schools do not support the narrative of misery, abuse, neglect and murder. Most of these old photographs show children who look happy, healthy and well nourished, and often depict them enjoying a variety of indoor and outdoor activities.

The Sisters’ chronicles and the old photographs produce cognitive dissonance – how could such allegedly abused, neglected and malnourished children appear to be so healthy and happy?

When looking at these old photographs, and in particular the photograph of the Kamloops swimming pool, Canadians might want to reflect on the stories they have been told about the horrors of residential schools and ask themselves whether they have been told the truth.

That brings us back to the question of whether the May 27, 2021 announcement by Chief Casimir that the remains of 215 children had been found at Kamloops is true.

There is a way to find out, and Chief Manny Jules promised it would be done. On the CBC’s Fifth Estate program in January Chief Manny Jules promised that the alleged burial site in the old apple orchard in Kamloops would be excavated. That promise has not been kept, and until that promise is kept, and excavation takes place, it cannot be said that the human remains of 215 children were actually found last May.

In fact, there is no evidence to support the claim that children secretly died or were killed and buried in the old apple orchard. There are no names associated with these allegedly missing children, no lists of children who had gone missing or unaccounted for, no parents or relatives who claim that their child was among the 215.

Who are the 215 children allegedly buried there? No one has the slightest idea.

Not one of the many Indian Bands who sent children to the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, including the Kamloops Band itself, has ever come forward with the name of a single child who allegedly went to the school and never returned, and for whom the Band has been looking ever since. Not one.

There is thus absolutely no evidence of any child who attended KIRS from any Band in BC actually having gone missing, much less that any child was murdered and secretly buried in the apple orchard by six year olds. That tale appears to be the figment of overactive imaginations.

There is one way to solve this perplexing issue once and for all. An excavation, as Chief Manny Jules promised. Excavation would bring clarity to the situation, it would help bring closure to First Nations people grieving and struggling with the situation, and it could help our country heal.

Brian Giesbrecht is a retired judge of the Provincial Court of Manitoba, Nina Green is an independent researcher, and Tom Flanagan is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary.