After decades in relative obscurity – the domain of mathematicians, computer experts, futurists and military researchers – artificial intelligence has been creeping into public consciousness. More and more products and processes boast of being “AI-enabled.” Reports seep out of China of entire factories and seaports being “run by AI.” Although it all sounds very promising – if slightly menacing – much of the AI discussion has remained vague and confusing to people not of a technical bent. Until one AI creation burst out of this epistemic fog, thrust into the cultural mainstream and proliferated in a digital blur: ChatGPT.

Within weeks of its appearance last November, millions of people were using ChatGPT and today it’s on just about everyone’s lips. Mainly, this is because it’s so darned useful. With ChatGPT (and several similar generative AI systems put out by competitors) the barely literate can instantly “create” university-grade essays or write poetry, the colour-blind can render commercial-grade graphics and even works of art, and wannabe directors can produce videos using entirely digital “actors” while ordering up the needed screenplays. The results are virtually if not completely indistinguishable from the “real thing.” Generative AI is showing signs of becoming an economic and societal disruptor. And that is the other big source of the surrounding buzz.

For along with its usefulness, ChatGPT is also deeply threatening. It offers nearly as much potential for fakery as creativity – everything from students passing off AI-generated essays as their own work to activist artists posting a deep-fake video of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg vowing to control the universe. Critics have warned it would facilitate more convincing email scams, make it easier to write computer-infecting malware, and enable disinformation and cybercrime. Some assert using ChatGPT is inherently insincere. Among myriad examples, a reddit user boasted of having it write his CV and cover letters – and promptly wrangling three interviews. A chemistry professor gave himself the necessary woke cred with a canned diversity, equity and inclusion statement for his job application. Two U.S. lawyers were fined for citing non-existent case law that, they maintained, had been entirely concocted by ChatGPT – including fake quotes and citations.

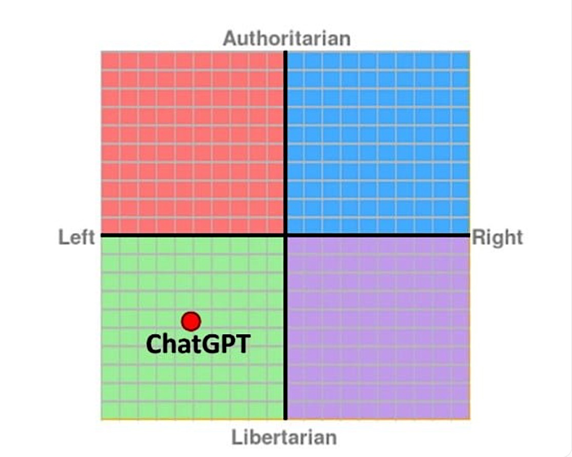

Then there’s the issue of politics. Though its defenders claim ChatGPT merely reflects what is on the internet – meaning it is fundamentally amoral – and others have described it as “wishy-washy,” some commentators claim to have detected a distinct left-wing bias. Asked in one exercise to write an admiring poem about Donald Trump, ChatGPT claimed it couldn’t “generate content that promotes or glorifies any individual.” Yet it had no problem doing just that for Joe Biden, cranking out the cringeworthy lines: Joe Biden, leader of the land,/with a steady hand, and a heart of a man. One U.S. researcher testing ChatGPT’s political leanings found it to be against the death penalty and free markets, and in favour of abortion, higher taxes on the rich and greater government subsidies.

The mushrooming popularity of generative AI tools makes this issue of acute interest – especially given that millions of users won’t be alert to potential political biases or attempts to manipulate them. Finding out where ChatGPT sits on the political spectrum seems rather important. So is determining whether the bot might be amenable to being influenced by its human interlocutors. Can the artificial intelligence, in other words, learn anything and gain any wisdom from the natural kind? The research process underlying this essay aimed to find out.

Read the full op-ed at C2CJournal.ca.