Hymie Rubenstein is editor of The REAL Indian Residential Schools newsletter and a retired professor of anthropology, The University of Manitoba

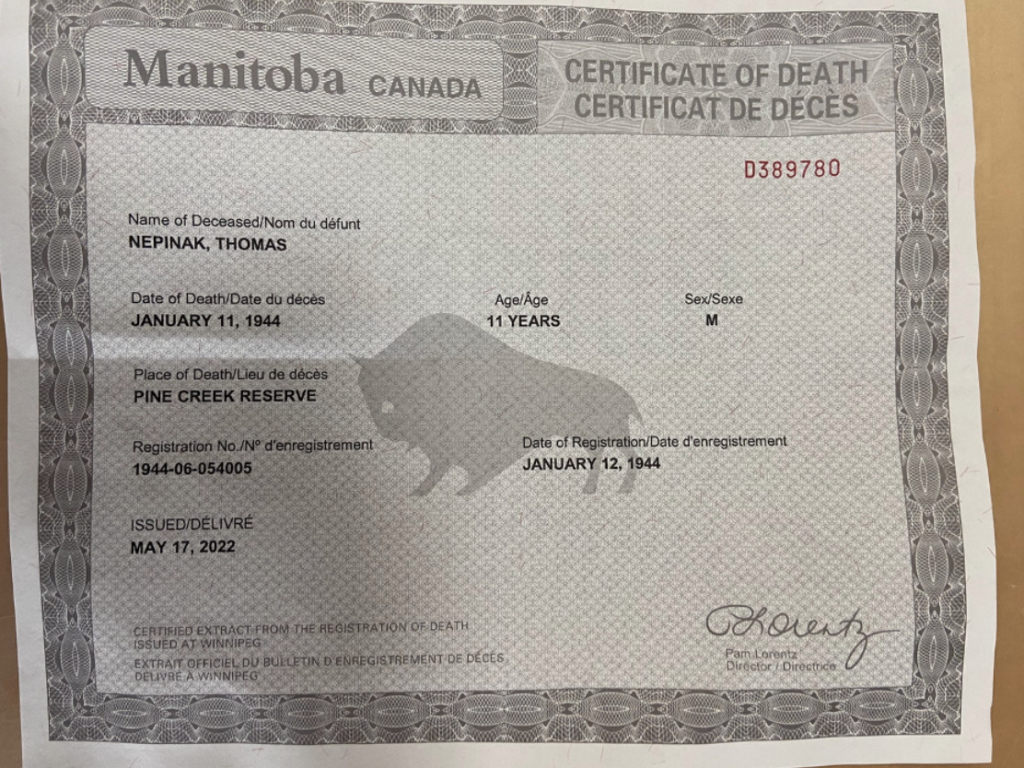

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of the discovery of the fate of Thomas Nepinak, an eleven-year-old Indian Residential School (IRS) student who died in 1944. My preliminary discussion lacked evidence which I have now located: Thomas’s death certificate as well as one for another reputed Indian Residential School student.

While superficially based on a May 24 CBC news report about yet another ground penetrating radar (GPR) study, this time on the Pine Creek Indian Reserve in Manitoba, and an attempt by a distant relative to find out what happened to Thomas Nepinak after he died at the school, there is far more to this story than meets the eye.

The second missing student is Roderick Charlie. Roderick died in 1941 at the age of 11 in a hospital in Victoria, British Columbia, and was buried nearby.

These two cases go to the heart of the uncertainty surrounding both the thousands of missing children listed on the Memorial Register of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) and those claimed to be buried in unmarked graves across Canada.

These totally different issues have been deliberately or sloppily conflated:

(1) the hundreds of alleged but unproven burial plots “discovered” in mainly named reserve cemeteries by the error-prone technique called GPR have found not a single missing IRS student;

(2) the 4,115 students on the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation’s Memorial Register, all but a handful of whom have a name and date of death attached to them. Invariably, these former students are also referred to as “missing.” But they are not missing because they are known to be dead. Their cause of death, place of death, and place of burial is slowly being revealed by impartial researchers, as shown below.

The sole purpose of this conflation is to imply that many or most named Memorial Register children are lying in the newly discovered GPR soil disturbances and thousands more that are still to be found. This can be gleaned from the following NCTR statement:

The discovery of an unmarked mass burial site at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School [as announced on May 27, 2021] highlights the urgent need for a concerted national response on behalf of all the children who were stolen from their families and who never returned home [those named in the Memorial Register]….

Canada’s failure to properly investigate and protect the sites where our sisters and brothers were buried means that we still do not have the whole truth. Too many of these children have never been identified by name and have never been located….

Claiming that “Too many of these children have never been identified by name and have never been located” implies that the turned earth findings at Kamloops contain such children even though “too many” should be “none” when referring to the contents of these soil disturbances. So does lumping the not-missing children on the Memorial Register with the contents of the soil disturbances in an abandoned apple orchard near the Kamloops IRS.

The interview of one band member in the CBC story claiming that she has been searching for a distant missing relative nicely captures this conflation:

“His name is Thomas and he was 11…. He never came home from residential school, so everyone is looking forward to hopefully getting his remains so they can do a proper burial for him.”

However, Thomas whose tragic death at such a tender age has now been revealed was never missing. His is the last name on the Pine Creek IRS Memorial Register, as mentioned in my previous discussion. At most, he was slowly forgotten over the decades by most of his family after he died, possibly of blunt force trauma. Since the reserve has always had its own community cemetery, he would have certainly been interred there in a grave whose wooden cross has long since disintegrated. He surely had “a proper burial,” as have thousands of his “missing” peers.

His notarized death certificate provides conclusive proof of where he was born and where he died. It gives the date of his death and how old he was when he died. Although his surname was not mentioned by his alleged great-niece, Jennifer Rocchio, it would be past coincidental that an eleven-year-old child by the name of Thomas Nepinak, a student at Pine Creek IRS, listed as having died at the same age and same year, is not the same person.

Thomas is one of only two named individuals on the NCTR’s missing children Memorial Register who a named relative is searching for. How can this be so? If there are so many missing children, why are no family members looking for them?

As for the other missing student, Roderick Charlie, a copy of his death certificate was located by the Wall Street Journal on behalf of his great-nephew, Russell Williams, which indicates Roderick died of tuberculosis after nearly a year in hospital. His family suspects he was transferred there from the Kamloops Indian Residential School where they claim he was a student. But his name does not appear on the Memorial Register for that or any other Indian Residential School.

But there is one non-relative — a determined and objective researcher named Nina Green — who has been looking for and finding hundreds of such children for months now. Some of her discoveries are found here and here based on painstaking searches of the relevant archives. These records show that all were buried in named cemeteries mainly on their home reserves.

Murray Sinclair, former Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, seems intent on erroneously lumping the 4,115 children like Thomas listed in the Memorial Register with the few hundred inconclusive GPR soil anomalies found on several reserves since the end of May 2021. And he is very keen also to grossly inflate the latter by claiming without any evidence that “15,000 to 25,000 … maybe even more” IRS children may be missing.

Thousands more children like Thomas could easily be found where precise information about them is buried, namely in carefully preserved school, church, and government records.

With files from Nina Green.

Hymie Rubenstein is editor of The REAL Indian Residential Schools newsletter and a retired professor of anthropology, The University of Manitoba